Contraception & Menstrual Management

Although rates of sexual activity, pregnancies, and births among adolescents have continued to decline during the past decade to record lows, 40% of high school students have had sex (Adolescent and School Health (CDC)). As a result, sexually transmitted infections (STIs) and unintended pregnancies remain significant public health problems. [Grubb: 2020]

Most teen pregnancies are unintended, and half result from contraception misuse. [Pritt: 2017] Only 2-3% of contraceptive users ages 15-19 use the most effective methods. [Lindberg: 2016] [Martinez: 2015] [Santelli: 2007] [Kavanaugh: 2015] Long-acting reversible contraceptives (LARC), which include intrauterine devices (IUDs) and etonogestrel implants, are the most effective forms of contraception, with less than 1% of users becoming pregnant in the first year of use. [Menon: 2020] In addition to counseling that abstinence is the most effective contraception, primary care clinicians are encouraged to provide adolescents with education on sexual and reproductive health, including teens with developmental or physical disabilities. Primary care clinicians should also provide screening for STIs, vaccinations, contraceptive counseling, and guidance to promote healthy lifestyle choices. [Grubb: 2020]

Prognosis

Other Names

LARC (long-acting reversible contraceptives)

Oral contraceptive pill (OCP)

Pregnancy prevention

Sexual health

Billing and Coding for Contraception Services

Z11.3, Encounter for screening for infections with a predominantly sexual mode of transmission

Z30.01x, Encounter for initial prescription of contraceptives (requires further level of detail denoting which form of contraception), e.g.,

- Z30.014, Encounter for initial prescription of intrauterine contraceptive device

- Z30.017, Encounter for initial prescription of implantable subdermal contraceptive

- Z30.019, Encounter for other general counseling and advice on contraception

- Z30.4x, Encounter for surveillance of contraceptives (requires further level of detail denoting which form of contraception

Z70.8, Other sex counseling (counseling on prevention of sexually transmitted illnesses)

Z70.9, Sex counseling, unspecified

Z72.5x, High-risk sexual behavior (requires further level of detail about sexual orientation)

CPT 11981, Insertion, non-biodegradable drug delivery implant

CPT 11982, Removal, non-biodegradable drug delivery implant

CPT11983, CPT11983, Removal with reinsertion, non-biodegradable drug delivery implant

HCPCS J7307, Etonogestrel implant

CPT 58300, Insertion of IUD

CPT 58301, Removal of IUD

HCPCS J7298, Levonorgestrel IUD Mirena

HCPCS J7300, Copper IUD

HCPCS J7301, Levonorgestrel IUD Skyla

2.9 MB).

2.9 MB).

Pearls & Alerts

Adolescents with Special Health Care Needs

Adolescents with chronic illnesses and those with physical or mental

disabilities have sexual health and contraceptive needs similar to their peers and

require the same education and care in a developmentally appropriate context. These

children are at increased risk of abuse.

At-Risk Youth

Stressful situations in childhood, such as being raised by a single

parent, exposure to community or domestic violence, and being in the foster care

system, are associated with higher rates of sexual activity among minors. School

attendance has been found to be protective. [Brahmbhatt: 2014] These adolescents experience unplanned pregnancies at

higher rates than their peers, suggesting that they have higher rates of unmet

reproductive health care needs. [Barnert: 2016]

[Council: 2015]

HPV Vaccine

HPV vaccines are recommended for males and females from ages 9-26,

regardless of sexual activity.

Bone Mineral Density

While there has been some concern in the past about the effect that

depot medroxyprogesterone acetate (Depo-Provera) has on bone mineral density, the

effect has been found to be reversible. [American: 2017]

Furthermore, the use of “Depo” does not appear associated with increased risk of

fragility fractures. However, because of its effects on bone density, limiting use

to 2 years is advised whenever feasible. [Fouquier: 2015]

See Osteoporosis and Pathologic Fractures.

Over-the-Counter Contraception

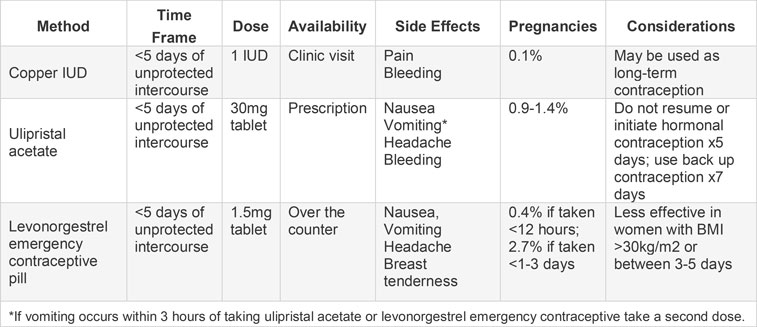

Emergency contraception, aka “morning-after pills,” such as Plan B

One-Step, is available without a prescription and do not require identification to

purchase. Condoms may be obtained over the counter at any age.

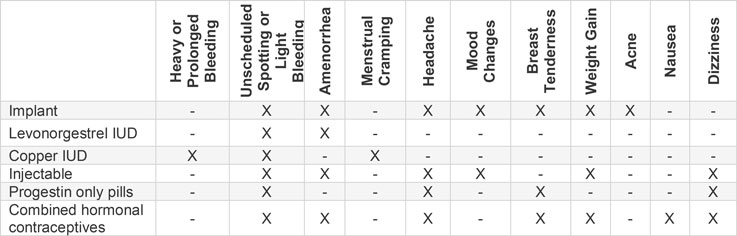

Contraception to Treat Irregular Bleeding

To treat irregular bleeding (e.g., spotting, heavy bleeding,

prolonged bleeding) while using a hormonal method such as an implant or injectable,

consider NSAIDs for 5-7 days during bleeding days and combined oral contraceptives

or estrogen for 10-20 days (see U.S. Selected Practice Recommendations for Contraceptive Use (CDC)).

Immobility

Special consideration should be taken when selecting contraceptives

for adolescent females with prolonged immobility in a bed or wheelchair dependence.

Consider the risk of loss of bone density with long-term Depo-Provera use as well as

the risk of deep vein thrombosis (DVT) from use of estrogens. Whenever possible,

encourage use of a stander or walker on a daily basis to promote bone health.

Monitor Vitamin D3 levels annually and supplement if indicated. See Calcium and Vitamin D for more details.

STI Testing and IUD Placement

A known GC/CT infection is a contraindication

to IUD insertion. Testing is not necessary prior to insertion and should not delay

insertion. Testing can be done with insertion, and the IUD can remain in place if a

test result is positive.

Education & Access

Contraceptive counseling should occur before onset of sexual activity. The AAP recommends LARC as the first-line method to prevent pregnancy for sexually active teens. [Menon: 2020] To prevent STDs, LARC methods must be augmented by condom use.

Sexual Health Counseling at Well-Child Visits

Early adolescence (generally ages 11-14) begins with the onset of puberty and accompanying physical and emotional changes. Intercourse at this age is uncommon; sexual activity alerts the clinician to an unsafe situation. Introducing sexual health topics at well-child visits begins with the discussion of pubertal changes. To ensure children feel comfortable discussing reproductive health and sexuality, it is important to establish a rapport with the child and their caregivers to facilitate confidentiality (see Confidentiality, below). The clinician can help normalize pubertal changes, encourage abstinence, provide anticipatory guidance, and gauge the teen’s understanding of sex. [Richards: 2016] Involvement of trusted adults to discuss healthy behaviors and relationships with the adolescent is encouraged.

Exploration of identity and independence begins in middle adolescence (generally ages 14-17). Teens typically do not seek sexual health care until after first intercourse, which increases their risk of sexually transmitted infections and unintended pregnancy. Offering teen-friendly resources, like pamphlets and websites written for teens, can encourage independence and help the teen to feel more involved in their care.

About 71% of adolescents have had sexual intercourse by age 19. [Richards: 2016] Older teens have likely been exposed to varied information concerning contraception and sexual health. This information can range from current and factual to objectively false. Discuss this with them. Correct any misinformation and reinforce evidence-based information. Ask about goals for the future, specifically plans for starting a family and if this is something they desire. Counsel sexually active teens to always use condoms as a dual method to prevent pregnancy and STDs.

Reproductive health information should be provided to all sexually active adolescents, including gay, lesbian, and bisexual adolescents. Research indicates that these sexual minority adolescents are at higher risk for pregnancy than their peers due to earlier age of first sexual intercourse and more sexual partners. [Lindley: 2015] Women who have sex with women (WSW) are a diverse population and should not be presumed to be at low or no risk for STIs as a result of reported sexual behavior. Data suggests that genital transmission of HPV and HSV-1 and 2 may be more common in WSW. Men having sex with men who engage in high risk sexual behavior are at higher risks for HIV and STIs including higher rates of Hepatitis A and B and HPV (see 2015 Sexually Transmitted Diseases Treatment Guidelines: Special Populations (CDC)). Similarly, adolescents with chronic medical conditions or developmental disabilities should receive sexual and reproductive health information, though it may need to be adapted to their developmental level. [Committee: 2014] Hence, all adolescents, regardless of the gender of their sexual partners, should have access and education around safe sex practices, contraception, and preventive medicine.

Access to Birth Control

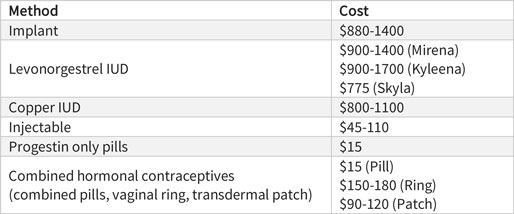

The 2010 Affordable Care Act requires private insurers to cover FDA-approved contraceptive methods and contraceptive counseling at no cost to the patient when delivered by a network provider; however, states define family planning benefits and regulate payments made to providers and insurers. Low-cost and free contraception may be available at Title X family planning clinics, which can be found at Find a Family Planning Clinic (HHS).

Minors with private insurance coverage must abide by state laws, which may require parental consent. The Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA) allows parents to access a child’s health records unless state law prohibits disclosure or the parent agrees to let their child receive confidential care. [Kumar: 2016] Adolescents and pediatricians express concerns over confidentiality related to contraception. The right to consent does not guarantee confidentiality as electronic health records create breaches in standard practice. Parents or guardians can request medical records such as discharge summaries, appointment information, and notifications, and these can include contraception details. Thus, adolescents can be wary about pursuing contraception even when state laws allow for confidential reproductive health care for teens. [Menon: 2020]

Assessment

Current & Past Medical History

- Partners: Ask about the number and gender of current and past sexual partners. Do not make assumptions based on sexual preference or gender identity.

- Practices: Ask about sexual contact (anal, oral, vaginal).

- Protection: Ask about condom use.

- Past STDs: Ask about past diagnoses, treatments, and current symptoms for both the patient and partner.

- Prevention: Ask about plans for pregnancy and use of contraception.

Comorbid Conditions

1017 KB)

(Home environment, Education and

employment, Eating, peer-related

Activities, Drugs,

Sexuality, Suicide/depression, and

Safety from injury and violence ) can alert the clinician

to risky behaviors and unsafe situations associated with sexual activity, such

as abuse and substance use. [Zieman: 2016]

1017 KB)

(Home environment, Education and

employment, Eating, peer-related

Activities, Drugs,

Sexuality, Suicide/depression, and

Safety from injury and violence ) can alert the clinician

to risky behaviors and unsafe situations associated with sexual activity, such

as abuse and substance use. [Zieman: 2016]

Although adolescents and young adults (15-24 years of age) in the United States account for only 1/4 of the sexually active population, they acquire 1/2 of new STIs. [Satterwhite: 2013]

Children with a history of abuse or neglect are more likely to initiate sexual activity at a younger age and have more pregnancies than their peers. [Negriff: 2015] A history of abuse alerts the clinician to the possibility of risky sexual behavior. For children 14 years old and younger, intercourse is uncommon and alerts the clinician to the possibility of abuse. [Richards: 2016]

About 1:5 sexually active teens used drugs or alcohol before having last sexual intercourse (see Adolescent and School Health (CDC)). Children of substance abusers are more likely to engage in risky sexual behavior. [Skinner: 2014] The Portal's Substance Use Disorders provides assessment and management information.

Physical Exam

Do not use contraceptives containing estrogen in adolescents with a systolic pressure of ≥160 mmHg, diastolic pressure of ≥100 mm Hg, or vascular disease. [Curtis: 2016]

Screening for obesity is not necessary for the safe initiation of contraceptives. Calculating baseline BMI may be helpful for monitoring changes if the adolescent is concerned about weight change perceived to be associated with their contraceptive method. [Curtis: 2016] Obesity is not a contraindication to emergency contraceptive use as well as the Nexplanon as some studies suggest a BMI >30 may increase the risk of pregnancy and clots when taking levonorgestrel emergency contraceptive pills, etonogestrel implant, or ulipristal acetate. [Curtis: 2016]

Breast examination is not necessary for the safe initiation of contraceptives. [Curtis: 2016]

A pelvic exam is not indicated for initiation of contraception except in presence of abnormal discharge, bleeding, or pelvic pain. [Raidoo: 2015] A pelvic exam is necessary for IUD insertion to assess for uterine size, position, and any cervical or uterine abnormalities that may prevent insertion. [Curtis: 2016] Be aware that performing a pelvic exam on an adolescent with spinal cord injury above T6 may lead to autonomic dysreflexia. [Fouquier: 2015]

Testing

Pregnancy

Testing for pregnancy is not necessary before initiating

contraception, but it is good practice, particularly for patients who may

not be accurate historians. It is strongly recommended to perform a

pregnancy test before inserting anything into the uterus.

The following considerations can help clinicians be reasonably certain a woman is not pregnant if she has no symptoms of pregnancy:

- It has been <7 days after start of normal menses.

- It has been <7 days after spontaneous or induced abortion.

- The woman has not had sexual intercourse since start of last normal menses.

- The woman has been correctly and consistently using a reliable method of contraception.

- The woman is within 4 weeks postpartum. [Curtis: 2016]

- The woman is fully or nearly fully breastfeeding and <6 months postpartum.

Sexually Transmitted Infections

Screen all sexually active adolescents annually for

chlamydia and gonorrhea. The USPSTF recommends testing all sexually active

adolescents ages 15 and older for HIV. Screening tests for STIs are not

required for placement of IUDs or use of contraception if the patient is

without risk factors. [Curtis: 2016]

With the new data reflected by the CDC recommendations, researchers have found that IUDs are not significantly associated with upper genitalia tract infections [Curtis 2016]. Delaying placement is only recommended if purulent cervicitis is examined or if a known gonorrhea or chlamydia infection has not been treated. [Curtis: 2016]

Screening or testing for syphilis, Hepatitis B, Hepatitis C, herpes, and trichomonas are based on risk factors. HPV testing or cervical cancer screening is not recommended for women <21 years of age. In-depth guidelines can be found at Sexually Transmitted Diseases: Screening Recommendations and Considerations (CDC).

Contraindications & Drug Interactions

Most contraceptive methods are safe for use by all people. The Medical Eligibility Criteria for Contraceptive Use (CDC) ( 170 KB) groups

contraceptive methods into categories that indicate safety when used by adolescents

with specific health conditions. [Curtis: 2016] The

categories are:

170 KB) groups

contraceptive methods into categories that indicate safety when used by adolescents

with specific health conditions. [Curtis: 2016] The

categories are:

- MEC 1: No restriction for the use of the contraceptive method

- MEC 2: Advantages of using the method generally outweigh the risks

- MEC 3: Risks usually outweigh the advantages of using the method

- MEC 4: Unacceptable health risk if the contraceptive method is used

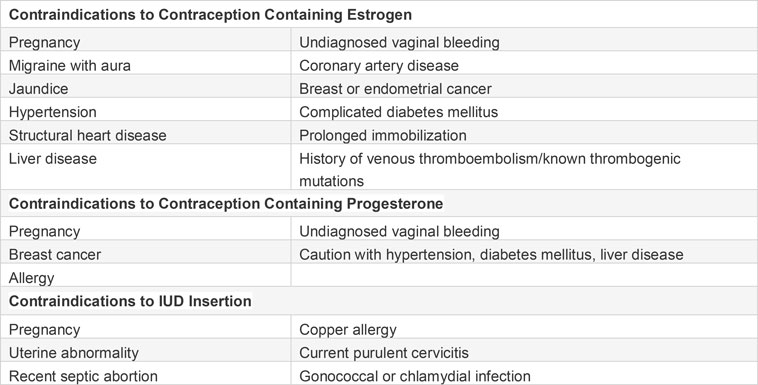

The MEC is accessible in a free app from the CDC and shows contraindications sorted

by both method and medical condition. Links to download the app can be found in the

Downloads and Resources section of Medical Eligibility Criteria for Contraceptive Use (CDC) ( 170 KB). A summary of

contraindications for contraception use is listed in the following

table.

170 KB). A summary of

contraindications for contraception use is listed in the following

table.

Contraindications

A known GC/CT infection is a contraindication to IUD insertion. Testing is not necessary prior to insertion and should not delay insertion. Testing can be done with insertion, and the IUD can remain in place if a test result is positive.

Oral Contraceptives and Antibiotics

With the exception of rifamycins, previous concerns about concurrent

use of contraceptives and antibiotics are not supported by recent evidence.

[Simmons: 2018] recent evidence. A clinically

concerning drug interaction between oral contraceptive pills and rifampin and

rifabutin has been found, though data are limited for other rifamycins. [Simmons: 2018] The CDC categorizes oral contraception

interactions with rifampin and rifabutin as MEC 3: risks usually outweigh the

advantages of using the method.

Oral Contraceptives and Antiepileptic Drugs

Most drug-drug interactions are due to distinct mechanisms, making

them predictable and avoidable. Antiepileptic drugs and most contraceptives,

particularly oral and combined hormonal contraceptives, are metabolized by the

liver, affecting effectiveness of both. Antiepileptic drugs regarded as compatible

for use with oral contraception are valproate, gabapentin, levetiracetam,

zonisamide, and lacosamide. [Reimers: 2015] Antiepileptic

drugs that may increase the risk of unplanned pregnancy with oral contraception are

carbamazepine, lamotrigine, phenobarbital, and phenytoin. [Reimers: 2015] These drugs, in addition to oxcarbazepine, topiramate, and

primidone are rated as MEC 3 - risks usually outweigh the advantages of use.

[Curtis: 2016] Some experts advise increasing the

estrogen component of combined oral contraceptives to 50 μg (micrograms) (= 0.05 mg)

for those taking antiepileptic drugs simultaneously; others such as at Planned

Parenthood recommend 30 μg (= 0.03 mg) and skipping placebo pills when using

lamotrigine or doses of topiramate >200. [Fouquier: 2015]

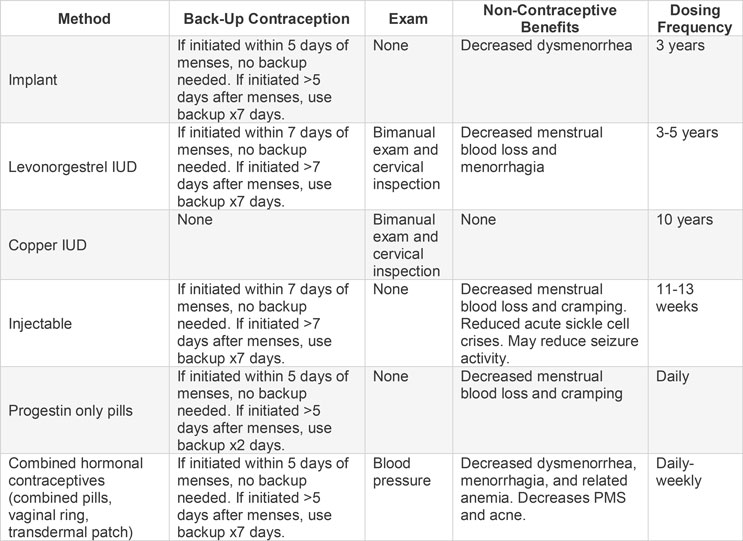

Management

The following information focuses on contraception. Recall also that hormonal contraceptives are often used to manage menstruation. Before making a contraceptive recommendation, ask about goals for menstrual management (i.e., reduce or eliminate flow, improve predictability, control timing of periods, reduce associated symptoms, reduce caregiver burden). For example, a person with heavy bleeding during periods may benefit from a levonorgestrel IUD more than a copper IUD. Athletes may prefer skipping oral contraceptive placebo pills to avoid dates when they prefer not to menstruate.

Contraception for Adolescents with Special Health Needs

170 KB) for

details about medical conditions and medications that pose risks to

contraceptive use, and see [Carmine: 2018] for

summarized guidance from the World Health Organization (WHO) and CDC on

prescribing contraceptives for adolescents with: morbid obesity, migraine

headache, cardiac conditions, hypertension, diabetes mellitus, hyperlipidemia,

systemic lupus erythematosus, sickle cell anemia, cystic fibrosis, inflammatory

bowel disease, or seizure disorders, including discussion of benefits vs risks.

170 KB) for

details about medical conditions and medications that pose risks to

contraceptive use, and see [Carmine: 2018] for

summarized guidance from the World Health Organization (WHO) and CDC on

prescribing contraceptives for adolescents with: morbid obesity, migraine

headache, cardiac conditions, hypertension, diabetes mellitus, hyperlipidemia,

systemic lupus erythematosus, sickle cell anemia, cystic fibrosis, inflammatory

bowel disease, or seizure disorders, including discussion of benefits vs risks.

Adolescents are eligible for all contraceptive methods, regardless of pregnancy history. [Zieman: 2016] All contraceptive methods can be started on the day of visit, regardless of menstrual cycle timing, if the clinician is reasonably sure the patient is not pregnant. If a patient desires LARC and is unable to receive it that day due to cost or privacy concerns, it is acceptable to use either combined hormonal contraceptives or depot medroxyprogesterone acetate injection (DMPA) until LARC can be inserted. Wait 5 days to start birth control methods containing progesterone for those who have used the emergency contraceptive ulipristal acetate. [Apter: 2017]

Changing Contraception Methods

Emergency Contraception (EC)

Resources

Information & Support

For Professionals

Adolescent Health Curriculum (PRH)

A comprehensive, evidence-based curriculum for residency programs, youth-serving health professionals, and self-guided learners

with PowerPoint modules and patient standardized case videos that are free to use, edit, and share; Physicians for Reproductive

Health.

U.S. Selected Practice Recommendations for Contraceptive Use (CDC)

Recommendations for health care providers from the July 29, 2016 / 65(4);1–66 Morbidity and Mortality Report from the Centers

for Disease Control and Prevention.

Center for Adolescent Health and Law

Promotes health care for adolescents, writes about the implications of the Affordable Care Act for adolescents and young adults,

and publishes (for a fee) detailed information about state laws that allow minors to consent for their own health care.

Coding for the Contraceptive Implant and IUDs (ACOG) ( 2.9 MB)

2.9 MB)

CPT and ICD-10 coding details for reimbursement of contraceptive services; American Congress of Obstetricians and Gynecologists

(updated 2018).

For Parents and Patients

All about Birth Control (Planned Parenthood)

Information about the effectiveness, safety, and use of most birth control methods.

Sex, Etc.

Information about sex by teens for teens.

TeenSource.org

Information for teens about birth control, relationships, and sexual health.

Planned Parenthood for Teens (Planned Parenthood)

Information about relationships, your body, and sexual health.

Scarleteen

Scarleteen is an independent, feminist, grassroots sexuality and relationships education media and support organization and

website providing sex and relationships information and support for young people worldwide (approximately ages 15-30). Has

a strong emphasis on diversity.

Practice Guidelines

Committee on Adolescence.

Contraception for adolescents.

Pediatrics.

2014;134(4):e1244-56.

PubMed abstract / Full Text

Curtis KM, Jatlaoui TC, Tepper NK, Zapata LB, Horton LG, Jamieson DJ, Whiteman MK.

U.S. Selected Practice Recommendations for Contraceptive Use, 2016.

MMWR Recomm Rep.

2016;65(4):1-66.

PubMed abstract / Full Text

The 2016 U.S. Selected Practice Recommendations for Contraceptive Use (U.S. SPR) addresses a select group of common, yet sometimes

controversial or complex, issues regarding initiation and use of specific contraceptive methods. The recommendations in this

report are intended to serve as a source of clinical guidance for health care providers and provide evidence-based guidance

to reduce medical barriers to contraception access and use.

Quint EH, O'Brien RF.

Menstrual Management for Adolescents With Disabilities.

Pediatrics.

2016;138(1).

PubMed abstract

This policy from the American Academy of Pediatrics Committee on Adolescence and the North American Society for Pediatric

and Adolescent Gynecology is designed to help guide pediatricians in assisting adolescent females with intellectual and/or

physical disabilities and their families in making decisions related to successfully navigating menstruation.

Patient Education

Birth Control Method Options (FPNTC) ( 142 KB)

142 KB)

1-page printable patient education guide to different kinds of birth control, efficacy, side effects, effects on menstruation,

and other important information; Family Planning National Training Center.

You and Your Sexuality: FAQs for Teens (ACOG)

Information that ranges from emotions and attraction to anal sex and rape; American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists.

Your First Gynecologic Visit: FAQs for Teens (ACOG) ( 162 KB)

162 KB)

Learn about what to expect when getting a pelvic exam or Pap test; American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists.

Tools

Find a Family Planning Clinic (HHS)

Search by city, state, or zip code to find a Title X family planning clinic; U.S. Health and Human Services.

HEEADSSS Assessment Guide (USU) ( 1017 KB)

1017 KB)

Examples of open-ended questions the clinician can ask adolescents about Home, Education/Employment, Eating, Activities, Drugs,

Sexuality, Suicide/Depression, and Safety.

Services for Patients & Families in New Mexico (NM)

| Service Categories | # of providers* in: | NM | NW | Other states (3) (show) | | NV | RI | UT |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Adolescent Medicine | 1 | 1 | 2 | 8 | 2 | |||

| Family Medicine | 8 | 1 | 71 | 60 | ||||

| Gynecology: Pediatric/Adolescent; Special Needs | 3 | 9 | ||||||

| Obstetrics & Gynecology | 1 | 6 | 19 | |||||

For services not listed above, browse our Services categories or search our database.

* number of provider listings may vary by how states categorize services, whether providers are listed by organization or individual, how services are organized in the state, and other factors; Nationwide (NW) providers are generally limited to web-based services, provider locator services, and organizations that serve children from across the nation.

Helpful Articles

Carmine L.

Contraception for Adolescents with Medically Complex Conditions.

Curr Probl Pediatr Adolesc Health Care.

2018;48(12):345-357.

PubMed abstract

This article summarizes evidence-based guidelines from both the World Health Organization (WHO) and the Centers for Disease

Control and Prevention (CDC) to support medical providers in the provision of contraceptives to adolescent patients with specific

medical conditions or characteristics including: morbid obesity, migraine headache, cardiac conditions, hypertension, diabetes

mellitus, hyperlipidemia, systemic lupus erythematosus, sickle cell anemia, cystic fibrosis, inflammatory bowel disease, and

seizure disorders.

Fouquier KF, Camune BD.

Meeting the Reproductive Needs of Female Adolescents With Neurodevelopmental Disabilities.

J Obstet Gynecol Neonatal Nurs.

2015;44(4):553-63.

PubMed abstract

The complexity of caring for female adolescents with neurodisabilities often overshadows normal biological changes. These

young women may require additional or individualized support as they adapt to normal puberty and sexual maturation. Many choices

are available to assist in managing menstrual problems, hygiene issues, and contraception. Special considerations regarding

contraceptive methods, sexual education, and improving service accessibility are explored for clinicians.

Marcell AV, Burstein GR.

Sexual and Reproductive Health Care Services in the Pediatric Setting.

Pediatrics.

2017;140(5).

PubMed abstract

Raidoo S, Kaneshiro B.

Providing Contraception to Adolescents.

Obstet Gynecol Clin North Am.

2015;42(4):631-45.

PubMed abstract

Authors & Reviewers

| Author: | Rebekah Birdsall, DNP-WHNP |

| Contributing Authors: | Jennifer Goldman, MD, MRP, FAAP |

| Emily Sierakowski, MD |

| 2018: first version: Rebekah Birdsall, DNP-WHNPA; Jennifer Goldman, MD, MRP, FAAPCA |

Page Bibliography

American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists’ Committee on Adolescent Health Care.

Committee Opinion No. 710: Counseling Adolescents About Contraception.

Obstet Gynecol.

2017;130(2):e74-e80.

PubMed abstract

Modern contraceptives are very effective when used correctly and, thus, effective counseling regarding contraceptive options

and provision of resources to increase access are key components of adolescent health care. The initial encounter and follow-up

visits should include continual reassessment of sexual concerns, behavior, relationships, prevention strategies, and testing

and treatment for sexually transmitted infections per the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention's guidelines.

Apter D.

Contraception options: Aspects unique to adolescent and young adult.

Best Pract Res Clin Obstet Gynaecol.

2017.

PubMed abstract

Barnert ES, Perry R, Morris RE.

Juvenile Incarceration and Health.

Acad Pediatr.

2016;16(2):99-109.

PubMed abstract

This article helps provide better understanding of the health status and needs of incarcerated youth. Opportunities exist

in clinical care, research, medical education, policy, and advocacy for pediatricians to lead change and improve the health

status of youth involved in the juvenile justice system.

Birgisson NE, Zhao Q, Secura GM, Madden T, Peipert JF.

Preventing Unintended Pregnancy: The Contraceptive CHOICE Project in Review.

J Womens Health (Larchmt).

2015;24(5):349-53.

PubMed abstract / Full Text

Brahmbhatt H, Kågesten A, Emerson M, Decker MR, Olumide AO, Ojengbede O, Lou C, Sonenstein FL, Blum RW, Delany-Moretlwe S.

Prevalence and determinants of adolescent pregnancy in urban disadvantaged settings across five cities.

J Adolesc Health.

2014;55(6 Suppl):S48-57.

PubMed abstract / Full Text

Carmine L.

Contraception for Adolescents with Medically Complex Conditions.

Curr Probl Pediatr Adolesc Health Care.

2018;48(12):345-357.

PubMed abstract

This article summarizes evidence-based guidelines from both the World Health Organization (WHO) and the Centers for Disease

Control and Prevention (CDC) to support medical providers in the provision of contraceptives to adolescent patients with specific

medical conditions or characteristics including: morbid obesity, migraine headache, cardiac conditions, hypertension, diabetes

mellitus, hyperlipidemia, systemic lupus erythematosus, sickle cell anemia, cystic fibrosis, inflammatory bowel disease, and

seizure disorders.

Committee on Adolescence.

Contraception for adolescents.

Pediatrics.

2014;134(4):e1244-56.

PubMed abstract / Full Text

Council on Foster Care; adoption, and Kinship Care.

Health Care Issues for Children and Adolescents in Foster Care and Kinship Care.

Pediatrics.

2015;136(4):e1131-40.

PubMed abstract / Full Text

Children and adolescents who enter foster care often do so with complicated and serious medical, mental health, developmental,

oral health, and psychosocial problems rooted in their history of childhood trauma. Ideally, health care for this population

is provided in a pediatric medical home by physicians who are familiar with the sequelae of childhood trauma and adversity.

As youth with special health care needs, children and adolescents in foster care require more frequent monitoring of their

health status, and pediatricians have a critical role in ensuring the well-being of children in out-of-home care through the

provision of high-quality pediatric health services, health care coordination, and advocacy on their behalves. American Academy

of Pediatrics Policy Statement.

Curtis KM, Jatlaoui TC, Tepper NK, Zapata LB, Horton LG, Jamieson DJ, Whiteman MK.

U.S. Selected Practice Recommendations for Contraceptive Use, 2016.

MMWR Recomm Rep.

2016;65(4):1-66.

PubMed abstract / Full Text

The 2016 U.S. Selected Practice Recommendations for Contraceptive Use (U.S. SPR) addresses a select group of common, yet sometimes

controversial or complex, issues regarding initiation and use of specific contraceptive methods. The recommendations in this

report are intended to serve as a source of clinical guidance for health care providers and provide evidence-based guidance

to reduce medical barriers to contraception access and use.

Curtis KM, Tepper NK, Jatlaoui TC, Berry-Bibee E, Horton LG, Zapata LB, Simmons KB, Pagano HP, Jamieson DJ, Whiteman MK.

U.S. Medical Eligibility Criteria for Contraceptive Use, 2016.

MMWR Recomm Rep.

2016;65(3):1-103.

PubMed abstract

Division of STD Prevention, National Center for HIV/AIDS, Viral Hepatitis, STD, and TB Prevention, Centers for Disease Control

and Prevention.

Sexual Risk Behaviors: HIV, STD, & Teen Pregnancy Prevention.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; (2017)

https://www.cdc.gov/std/prevention/screeningreccs.htm. Accessed on 4/4/18.

Fouquier KF, Camune BD.

Meeting the Reproductive Needs of Female Adolescents With Neurodevelopmental Disabilities.

J Obstet Gynecol Neonatal Nurs.

2015;44(4):553-63.

PubMed abstract

The complexity of caring for female adolescents with neurodisabilities often overshadows normal biological changes. These

young women may require additional or individualized support as they adapt to normal puberty and sexual maturation. Many choices

are available to assist in managing menstrual problems, hygiene issues, and contraception. Special considerations regarding

contraceptive methods, sexual education, and improving service accessibility are explored for clinicians.

Grubb LK.

Barrier Protection Use by Adolescents During Sexual Activity.

Pediatrics.

2020;146(2).

PubMed abstract

This update of the 2013 AAP Committee on Adolescence policy statement is intended to assist pediatricians in understanding

and supporting the use of barrier methods by their patients to prevent unintended pregnancies and STIs and address obstacles

to their use.

Kavanaugh ML, Jerman J, Finer LB.

Changes in Use of Long-Acting Reversible Contraceptive Methods Among U.S. Women, 2009-2012.

Obstet Gynecol.

2015;126(5):917-27.

PubMed abstract / Full Text

Kumar N, Brown JD.

Access Barriers to Long-Acting Reversible Contraceptives for Adolescents.

J Adolesc Health.

2016;59(3):248-253.

PubMed abstract

Lindberg L, Santelli J, Desai S.

Understanding the Decline in Adolescent Fertility in the United States, 2007-2012.

J Adolesc Health.

2016;59(5):577-583.

PubMed abstract / Full Text

The decline in U.S. adolescent fertility has accelerated since 2007. Modeling fertility change using behavioral data can inform

adolescent pregnancy prevention efforts.

Lindley LL, Walsemann KM.

Sexual Orientation and Risk of Pregnancy Among New York City High-School Students.

Am J Public Health.

2015;105(7):1379-86.

PubMed abstract / Full Text

Marcell AV, Burstein GR.

Sexual and Reproductive Health Care Services in the Pediatric Setting.

Pediatrics.

2017;140(5).

PubMed abstract

Martinez GM, Abma JC.

Sexual Activity, Contraceptive Use, and Childbearing of Teenagers Aged 15-19 in the United States.

NCHS Data Brief.

2015(209):1-8.

PubMed abstract

Menon S.

Long-Acting Reversible Contraception: Specific Issues for Adolescents.

Pediatrics.

2020;146(2).

PubMed abstract

A clinical report providing guidance on how the pediatrician can play a key role in increasing access to long-acting reversible

contraception for adolescents by providing accurate patient-centered contraception counseling and by understanding and addressing

the barriers to use; American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP)'s Committee on Adolescence.

Negriff S, Schneiderman JU, Trickett PK.

Child Maltreatment and Sexual Risk Behavior: Maltreatment Types and Gender Differences.

J Dev Behav Pediatr.

2015;36(9):708-16.

PubMed abstract / Full Text

Pritt NM, Norris AH, Berlan ED.

Barriers and Facilitators to Adolescents' Use of Long-Acting Reversible Contraceptives.

J Pediatr Adolesc Gynecol.

2017;30(1):18-22.

PubMed abstract

Quint EH, O'Brien RF.

Menstrual Management for Adolescents With Disabilities.

Pediatrics.

2016;138(1).

PubMed abstract

This policy from the American Academy of Pediatrics Committee on Adolescence and the North American Society for Pediatric

and Adolescent Gynecology is designed to help guide pediatricians in assisting adolescent females with intellectual and/or

physical disabilities and their families in making decisions related to successfully navigating menstruation.

Raidoo S, Kaneshiro B.

Providing Contraception to Adolescents.

Obstet Gynecol Clin North Am.

2015;42(4):631-45.

PubMed abstract

Reimers A, Brodtkorb E, Sabers A.

Interactions between hormonal contraception and antiepileptic drugs: Clinical and mechanistic considerations.

Seizure.

2015;28:66-70.

PubMed abstract / Full Text

Richards MJ, Buyers E.

Update on Adolescent Contraception.

Adv Pediatr.

2016;63(1):429-51.

PubMed abstract

Santelli JS, Lindberg LD, Finer LB, Singh S.

Explaining recent declines in adolescent pregnancy in the United States: the contribution of abstinence and improved contraceptive

use.

Am J Public Health.

2007;97(1):150-6.

PubMed abstract / Full Text

Satterwhite CL, Torrone E, Meites E, Dunne EF, Mahajan R, Ocfemia MC, Su J, Xu F, Weinstock H.

Sexually transmitted infections among US women and men: prevalence and incidence estimates, 2008.

Sex Transm Dis.

2013;40(3):187-93.

PubMed abstract

Simmons KB, Haddad LB, Nanda K, Curtis KM.

Drug interactions between non-rifamycin antibiotics and hormonal contraception: a systematic review.

Am J Obstet Gynecol.

2018;218(1):88-97.e14.

PubMed abstract

Skinner ML, Fleming CB, Haggerty KP, Catalano RF.

Sex risk behavior among adolescent and young adult children of opiate addicts: outcomes from the focus on families prevention

trial and an examination of childhood and concurrent predictors of sex risk behavior.

Prev Sci.

2014;15 Suppl 1:S70-7.

PubMed abstract / Full Text

Society for Adolescent Health and Medicine, American Academy of Pediatrics.

Confidentiality Protections for Adolescents and Young Adults in the Health Care Billing and Insurance Claims Process.

J Adolesc Health.

2016;58(3):374-7.

PubMed abstract

Zieman M, Hatcher RA, Allen AZ, Lathrop E, Haddad L.

Managing Contraception.

14th ed. Bridging the Gap Foundation;

2016.

http://managingcontraception.com/

Link to free preview

Get Help in New Mexico

Get Help in New Mexico