CPAP & Bilevel PAP for Children

Guidance for primary care clinicians treating children who require non-invasive continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP) or bilevel positive airway pressure (BIPAP) therapy

Other Names

- Bilevel positive airway pressure (BIPAP, BiPAP™, or BPAP)

- Continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP)

- Nasal CPAP

- Non-invasive ventilation

Key Points

- Continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP) is the most commonly used positive airway pressure (PAP) modality for treatment of pediatric obstructive sleep apnea (OSA).

- Bilevel positive airway pressure (BIPAP) therapy may be considered in children with obstructive sleep apnea (OSA) who do not respond to or tolerate CPAP therapy. BIPAP therapy with a backup rate may augment ventilation in children with hypercapnia due to respiratory insufficiency or abnormal respiratory drive.

- CPAP or BIPAP therapy should be initiated under the guidance of an experienced clinician. Acclimating a child to PAP therapy and achieving long-term adherence requires a high patient and caregiver commitment. Patients require frequent follow-up to assess compliance, tolerance, and efficacy of CPAP or BIPAP treatment.

Role of the Medical Home

Evaluation & Treatment of Sleep Problems

Support Ongoing Care

Sleep Hygiene Education

32 KB) provides a

printable, 2-page handout with 14 easy tips for good sleep hygiene in children

ages 0-13, and Behavioral Techniques to Improve Sleep has sleep advice to share

with parents.

32 KB) provides a

printable, 2-page handout with 14 easy tips for good sleep hygiene in children

ages 0-13, and Behavioral Techniques to Improve Sleep has sleep advice to share

with parents.

CPAP & BIPAP – How They Work

CPAP and BIPAP deliver air via contoured nasal or oronasal masks to maintain airway patency. These technologies are used in acute and chronic care settings, including the home environment. Their most common use in children is for the treatment of obstructive sleep apnea.

Continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP)

CPAP delivers a constant flow of pressurized air throughout the

breathing cycle, resulting in mechanical stenting of the airway and increased

functional residual capacity (the volume of air in the lungs at the end of

expiration). CPAP does not impact tidal volume (air volume in each breath).

Bilevel positive airway pressure (BIPAP)

BIPAP provides 2 different levels of pressure. The inspiratory

positive airway pressure (IPAP) provides greater pressure during inhalation to

augment tidal volume. The expiratory positive airway pressure (EPAP) provides lower

pressure during exhalation to maintain adequate mean airway pressure and improve

functional residual capacity. BIPAP also can be set with a respiratory rate to

maintain a certain minimum number of breaths per minute. When BIPAP is used in

children to treat conditions other than obstructive sleep apnea, a backup rate is

often required.

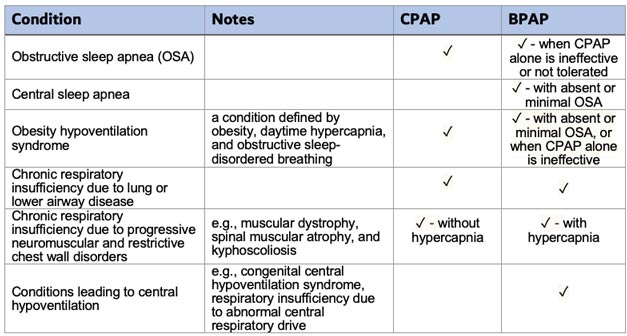

Indications for CPAP or BIPAP in Children

CPAP or BIPAP may be offered to children whose respiratory systems are compromised by airway obstruction, weakened respiratory muscles, decreased respiratory drive, or lung disease. In the home, CPAP and BIPAP machines are usually used only during sleep. In acute settings, CPAP or BIPAP may be an alternative to endotracheal intubation or weaning from mechanical ventilation.

Home CPAP or BIPAP may be considered for infants and young children weighing ≥5kg under certain clinical circumstances. In these patients, home CPAP/BIPAP should only be initiated under the guidance of an experienced pediatric provider who can evaluate the appropriateness and safety of home PAP therapy.

PAP Therapy Alternatives

For some children with OSA, alternatives and adjuncts to PAP therapy may include:

- Removal of the tonsils and/or adenoids (adenotonsillectomy)

- Other surgical interventions to relieve upper airway obstruction (septoplasty, nasal turbinate reduction, lingual tonsillectomy, tongue base reduction, maxillary or mandibular advancement surgery)

- Intranasal corticosteroids and leukotriene receptor antagonists

- Orthodontic maxillary expansion

- Weight loss in obese patients

- Tracheostomy in children with very severe OSA or significant upper airway obstruction during wakefulness

Initiation of PAP Therapy

- Children with suspected OSA should have an in-laboratory overnight polysomnogram for diagnosis and assessment of OSA severity prior to initiation of CPAP/BIPAP.

- The American Academy of Sleep Medicine has published guidelines for age-specific minimum and maximum positive airway pressure settings (see ‘Resources’ below).

- Nasopharyngeal obstruction can lead to substantial discomfort and intolerance of PAP therapy. Prior to initiating CPAP/BIPAP, the prescribing provider should evaluate the patient for nasal obstruction and treat if present.

- A properly fitting mask is required to ensure efficacy and patient comfort. The patient should undergo PAP mask fitting to determine the optimal interface.

- PAP desensitization and long-term adherence require a high patient and caregiver commitment. A strategy for PAP desensitization should be developed with the patient and caregiver and tailored to the child’s developmental and behavioral status.

- The patient and caregiver should receive education and a hands-on demonstration of CPAP/BIPAP device usage. The caregiver should be confident in operating the device.

- Caregiver training and support is a crucial aspect of pediatric CPAP/BIPAP therapy and often requires a multidisciplinary team (may include a clinician, psychologist, respiratory therapist, registered nurse, and/or pediatric sleep technician). Referral to a pediatric sleep center is recommended.

PAP Desensitization

- Modeling: The caregiver models PAP use in the clinic and then at home with the patient during the day.

- Graduated exposure: Introduce the PAP device and allow the child to touch/explore the equipment. Follow this by allowing the mask facepiece to be held in position on the face, then wearing the mask and headgear, followed by wearing the mask attached to PAP tubing with the machine on. Progression to the next step occurs when the child tolerates the current step well.

- Shaping: Gradually increase the amount of time the PAP mask is worn (during the day) or used (PAP machine turned on) during sleep. Use the ramp setting to gradually increase to prescribed pressure each time the device is turned on.

- Positive reinforcement: Give the child praise, caregiver affection, and small rewards for cooperating with wearing the PAP interface. Sticker charts or point systems can enforce nightly PAP use. With selective attention, the caregiver praises the patient for cooperative behavior; negative behavior is ignored.

- Escape prevention: If the child resists and attempts to pull off the mask, the caregiver or clinic staff distract the patient and redirect their hands away from the mask. The caregiver only removes the mask during calm cooperation.

- Distraction/counter-conditioning: Couple PAP therapy or mask use with a fun activity (e.g., as part of playtime, while reading a book, or watching a favorite video) during daytime desensitization or as part of the bedtime routine.

- Relaxation training: Provide the family and patient with instructions on guided imagery, progressive muscle relaxation, and/or diaphragmatic breathing to reduce anxiety and improve comfort when using PAP. See Apps to Help Kids and Teens with Anxiety.

Follow-Up & Evaluation

An overnight polysomnogram for titration of positive airway pressure settings is recommended in children who require home CPAP/BIPAP therapy. The timing of the PAP titration sleep study depends on the child’s age, developmental level, and clinical condition. Younger children and children with developmental disorders may require PAP introduction and desensitization prior to in-lab PAP titration.

Patients using nightly CPAP or BIPAP should regularly be seen by their specialty clinician. They should be encouraged to bring their equipment to clinic visits for verification of settings and troubleshooting treatment adherence. PAP compliance and efficacy data should be reviewed at every visit. Monitoring and addressing therapeutic side effects are also a part of the follow-up. Initial follow-ups may be as frequent as 1-2 times per month. Semiannual or annual follow-up may suffice once the patient has adjusted to therapy and is using PAP every night.

In children, normal growth and development, weight gain or loss, and changes in clinical condition can alter respiratory physiology and airway dynamics. Repeat evaluation with polysomnography and adjustment of PAP settings may be required.

Assessing Patient Response

Equipment

CPAP and BIPAP machines deliver a stream of heated, humidified, compressed air via a hose to a contoured mask worn over/under the nose or over the nose and mouth. This “splints” the airway (keeps it open with air pressure) so that unobstructed breathing becomes possible, reducing and/or preventing apneas (breathing stoppages) and hypopneas (shallow breathing). The masks are secured to the patient using accompanying elastic headgear.

The equipment generally includes:

- Flow generator (PAP machine): Provides continuous flow of pressurized air (measured in cmH2O). The machines are fairly small and quiet, weighing from 2 to 11 lbs. depending on the device and accessories.

- Power supply unit/cord: Most PAP devices are easily portable but require electricity. Patients who require PAP therapy during awake times or around-the-clock may need a more advanced device (home ventilator) with an internal battery for portable use.

- Water chamber/humidifier: Adds moisture and heat to inhaled air. Using heated humidified air improves most patients’ comfort and helps reduce side effects such as nose bleeds, dry mouth, voice changes, cough, and congestion.

- Air filter: Needs to be changed regularly.

- Hose/tubing: Tubing can be standard (non-heated) or heated. Heated tubing contains a heating coil to maintain air temperature and decrease condensation.

-

Mask: (see images below): For non-invasive ventilation to

be effective, a good mask fit and seal are crucial. There are several types

of PAP masks that a sleep specialist may offer based on the child’s needs

and preferences:

- Nasal mask: Covers the nose only

- Nasal pillow mask: Covers the nares only

- Oronasal mask (full face mask): Covers the mouth and nose

- Hybrid or minimal contact oronasal mask: Covers the mouth and nose, but the top of the mask rests under the nares (similar to nasal pillows)

Nasal Pillow PAP MaskNasal CPAP MaskOronasal Full-Face Mask

Care & Maintenance

Troubleshooting

- The PAP mask should be comfortable and appropriately sized for the patient’s face. It should not leak excessive air when attached to the hose and compressor. Noise that interferes with sleep is usually a sign of excessive air leak.

- A loose mask results in ineffective pressure delivery, excessive air leaks, and displacement during patient movement. A mask worn too tightly leads to air leaks through distortion of the mask-to-skin interface. Excessive pressure on the skin and facial bones also may increase the risk of skin breakdown and midface deformity.

- Protective barriers for skin may be considered if there is skin irritation.

- Eye irritation related to the mask or leaking air can be treated with lubricating drops, correcting the leak, and/or increasing humidification.

- PAP humidification, nasal hydration drops, nasal sinus rinse, and/or an intranasal steroid spray should be considered in patients with nasal dryness, congestion, or occasional nosebleeds.

- Most PAP machines have a “ramp” setting that initially delivers a set minimum pressure when turned on, followed by a gradual increase to the prescribed pressure.

- Some patients may experience difficulty exhaling when wearing PAP. Many devices have an “exhalation relief” setting that decreases the pressure at a set value (from 1-3 cmH2O) during exhalation.

- Mask liners may be used to prevent excess air leakage and reduce skin irritation and dermatitis.

- Flexible chin straps may be used in patients with nasal PAP masks to prevent excessive air leaks from open-mouth breathing. The straps are elastic enough that the patient can easily open their mouth if necessary.

- If the patient is experiencing suboptimal oxygen levels, oxygen can be delivered into the machine or mask using a supplemental oxygen adapter.

- Oronasal masks are generally avoided in children at high risk of aspiration.

Cost & Coverage of PAP

Depending on the device, CPAP/BIPAP systems can cost $500 to $8,000. Patients also can rent the equipment. Many major insurers, including Medicaid and Medicare, cover the cost of the technology for a range of diagnoses. Clinicians and patients are urged to contact the insurer to determine their specific guidelines. Although medical literature supports therapeutic effectiveness, FDA approval of pediatric home CPAP/BIPAP equipment is limited. In compliance with such guidelines, home care companies may refuse to cover certain patients, resulting in difficulty with patient access to care. Working with Insurance Companies has more information about Letters of Medical Necessity and appealing funding denials.

Resources

Information & Support

Related topics

For Professionals

Sleep Center - Healthcare Professional Resources (Cincinnati Children's)

Education, research, and treatment algorithm for pediatric clinicians.

American Academy of Sleep Medicine (AASM) Clinical Practice Guidelines

Evidence-based recommendations covering various sleep topics, including indications for pediatric polysomnography and recommendations

for titrating positive airway pressure therapy.

For Parents and Patients

Patient Resources: Pediatric Sleep Topics (ATS)

Fact sheets for patients and families about various sleep and breathing disorders in children and information on PAP therapy

for obstructive sleep apnea; American Thoracic Society.

Sleep Education (AASM)

Information about healthy sleep, sleep disorders, and a searchable directory of AASM-accredited sleep centers; American Academy

of Sleep Medicine.

Choosing a Mask (American Sleep Apnea Association)

Information about types of masks and alternative masks.

Non-Invasive Ventilation for Infants and Children (Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia)

PAP desensitization instructions for parents

Cleaning Your PAP Equipment (Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia)

Tips for cleaning the outside of the PAP machine, tubing, masks, and filters.

Avoiding 10 Common Problems with CPAP Machines (Mayo Clinic)

Advice on dealing with common problems associated with CPAP.

When Things Go Wrong with PAP (American Sleep Apnea Association)

Information about mask discomfort, nasal congestion, headache, ear pressure, and more.

Services for Patients & Families in New Mexico (NM)

| Service Categories | # of providers* in: | NM | NW | Other states (3) (show) | | NV | RI | UT |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Behavioral Therapies | 17 | 1 | 19 | 32 | 36 | |||

| Pediatric Otolaryngology (ENT) | 11 | 1 | 5 | 7 | 10 | |||

| Pediatric Pulmonology | 4 | 4 | 6 | 3 | ||||

| Pediatric Sleep Clinics [Discontinued] | ||||||||

| Sleep Disorders | 2 | 1 | ||||||

| Sleep Study/Polysomnography | 2 | 1 | 4 | |||||

For services not listed above, browse our Services categories or search our database.

* number of provider listings may vary by how states categorize services, whether providers are listed by organization or individual, how services are organized in the state, and other factors; Nationwide (NW) providers are generally limited to web-based services, provider locator services, and organizations that serve children from across the nation.

Helpful Articles

Parmar A, Baker A, Narang I.

Positive airway pressure in pediatric obstructive sleep apnea.

Paediatr Respir Rev.

2019;31:43-51.

PubMed abstract

Harford KL, Jambhekar S, Com G, Pruss K, Kabour M, Jones K, Ward WL.

Behaviorally based adherence program for pediatric patients treated with positive airway pressure.

Clin Child Psychol Psychiatry.

2013;18(1):151-63.

PubMed abstract

Hady KK, Okorie CUA.

Positive Airway Pressure Therapy for Pediatric Obstructive Sleep Apnea.

Children (Basel).

2021;8(11).

PubMed abstract / Full Text

Marcus CL, Brooks LJ, Draper KA, Gozal D, Halbower AC, Jones J, Schechter MS, Sheldon SH, Spruyt K, Ward SD, Lehmann C, Shiffman

RN.

Diagnosis and management of childhood obstructive sleep apnea syndrome.

Pediatrics.

2012;130(3):576-84.

PubMed abstract

Practice guideline focusing on uncomplicated childhood OSAS, (OSAS associated with adenotonsillar hypertrophy and/or obesity

in an otherwise healthy child); American Academy of Pediatrics.

Kushida CA, Chediak A, Berry RB, Brown LK, Gozal D, Iber C, Parthasarathy S, Quan SF, Rowley JA.

Clinical guidelines for the manual titration of positive airway pressure in patients with obstructive sleep apnea.

J Clin Sleep Med.

2008;4(2):157-71.

PubMed abstract / Full Text

Authors & Reviewers

| Authors: | Melissa A Maloney, MD |

| Jennifer N. Brinton, MD | |

| Senior Author: | Khanh Lai, MD, FAAP |

| Reviewer: | Brian McGinley, MD |

| 2022: update: Melissa A Maloney, MDA; Jennifer N. Brinton, MDA; Khanh Lai, MD, FAAPSA |

| 2022: update: Jennifer N. Brinton, MDA; Melissa A Maloney, MDA; Khanh Lai, MD, FAAPSA |

| 2011: revision: Nancy Murphy, MD, FAAP, FAAPMRR |

| 2011: update: Ameet S. Daftary, MDA |

| 2010: first version: Matt Pacenza, MAA |

Page Bibliography

Hady KK, Okorie CUA.

Positive Airway Pressure Therapy for Pediatric Obstructive Sleep Apnea.

Children (Basel).

2021;8(11).

PubMed abstract / Full Text

Harford KL, Jambhekar S, Com G, Pruss K, Kabour M, Jones K, Ward WL.

Behaviorally based adherence program for pediatric patients treated with positive airway pressure.

Clin Child Psychol Psychiatry.

2013;18(1):151-63.

PubMed abstract

Kushida CA, Chediak A, Berry RB, Brown LK, Gozal D, Iber C, Parthasarathy S, Quan SF, Rowley JA.

Clinical guidelines for the manual titration of positive airway pressure in patients with obstructive sleep apnea.

J Clin Sleep Med.

2008;4(2):157-71.

PubMed abstract / Full Text

Marcus CL, Brooks LJ, Draper KA, Gozal D, Halbower AC, Jones J, Schechter MS, Sheldon SH, Spruyt K, Ward SD, Lehmann C, Shiffman

RN.

Diagnosis and management of childhood obstructive sleep apnea syndrome.

Pediatrics.

2012;130(3):576-84.

PubMed abstract

Practice guideline focusing on uncomplicated childhood OSAS, (OSAS associated with adenotonsillar hypertrophy and/or obesity

in an otherwise healthy child); American Academy of Pediatrics.

Parmar A, Baker A, Narang I.

Positive airway pressure in pediatric obstructive sleep apnea.

Paediatr Respir Rev.

2019;31:43-51.

PubMed abstract

Get Help in New Mexico

Get Help in New Mexico